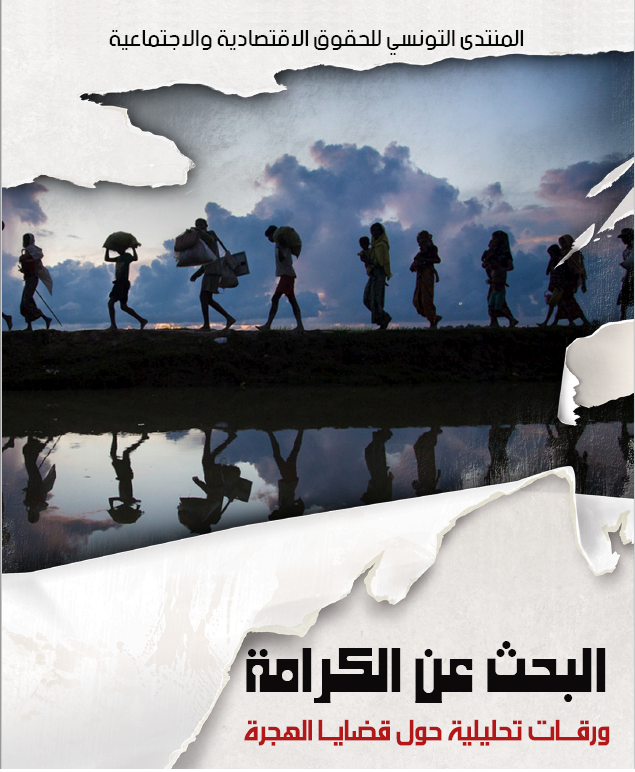

In Search of Dignity

Thwarting social protests and the project of irregular immigration: A sociological study on the causal link between social protests and irregular immigration

Khaled TABBABI

Abstract: Marie schneider

Introduction

Thousands of irregular migrants have died in the recent years in the desperate attempt to cross the Mediterranean in search of a better life. Despite numerous reports on the topic and recommendations for governments to ease their visa restrictions in order to facilitate legal migration and redirect migrants towards a safer route towards Europe, governments continue to draft legislation aimed at securing their borders rather than contributing to the saving of migrant lives. At the same time, ongoing economic, social and political crises in migrants’ countries of origin, assure a continuous flow of irregular migration, particularly among the Global South’s youth. This article aims at finding new factors playing into the phenomenon of irregular migration, with a focus on social movements and protest which often seem to prompt waves of irregular migrants departing from North Africa’s shores.

Problematic and Methodology

Tunisia, before and after the revolution, left little to no opportunity for its youth to improve their social status, emerge from poverty and escape marginalization on a global level. Desperate for change, they lent their support to numerous social movements, whether during the January revolution of 2011 or other movements before and after the revolution. These movements are national as well as regional and often continue over several years. The hypothesis underlying this research states that these campaigns’ failure is what drives youth to commit themselves to the dangerous migration routes crossing the Mediterranean.

Quantitative research, in the form of interviews with young activists who participated in protests in Sidi Bouzid, Kebili, Tataouine, Redeyef, Kasserine and Kerkennah after the revolution, intends to answer questions that would be left unanswered with a quantitative approach. The sample entailed 10 subjects, aged between 20 and 45, all from different regions and all with a history of attempted irregular migration. While every subject belonged to a different social movement, their attempt of migration differed too, with some having chosen to cross the Mediterranean, others having tried to migrate across land, e.g. the Moroccan Spanish borders. Some succeeded, some had been intercepted and others were deported. The intention with this sample was to show a small but diverse group’s experience, in order to be able to make suggestions for the larger population of young activists who had attempted to emigrate after their campaigns had failed. In order to analyze the data, a sociological approach was chosen, as it is most fit to explain social phenomena, by taking economic, social, cultural and political factors into account.

Social Movements and Irregular Migration Flow

While this summary will abstain from going into detail regarding the different social movements the subjects belong to, subjects and their movements have many things in common. Generally, campaigns grew out of a rising feeling of injustice and exclusion in the population which in turn were aggravated by a feeling of contempt for the political and social system. The demands of protesters include development, employment, adequate water supply, environmental regulations combating pollution, enhancement of infrastructure, health, education and social justice. In the majority of cases, protesters are suppressed violently by police, which led to several deceased protesters as well as countless injuries. Movements were supported by the Tunisian General Labor Union, as well as left wing political parties, who organize meetings and negotiations and determine approaches and forms of protests. However, some interviewees pointed out that the support of political parties is limited to election periods and possibly carries a political agenda. Regarding means of communication among protesters, subjects unanimously acknowledged the role social media plays in mobilization and awareness raising. Television is considered to be highly censored and generally not trusted among protesters who resort to networks like Facebook to spread the word.

Most of the interviewees have lost hope in the value and efficiency of democracy as a political system, particularly after the elections of 2014 did not seem to have any positive effect on the issues they were fighting for. They therefore take to social movements in search for advocacy of their social and economic rights. These movements provide a support system and give subjects the opportunity to collectively promote their rights. However, when these movements fail, subjects start looking for another alternative in order to climb up the social ladder. It is in these cases, when activists’ who previously found themselves lifted up by a movement they believed in, lose all hope in their country and the system in place and decide to take the step to emigrate.

The analysis of the interviews shows that push factors prevail over the pull factors in the case of emigrating Tunisian youth. The push factors even outweighed the fact that yearly hundreds of migrants die in the Mediterranean trying to cross over to European shores. The numbers published by the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights in 2016 and 2017 furthermore suggest that migration waves increase after every social protest ending in repression and the criminalization of activists. Particularly the repression of campaigns seems to be in a causal relationship with an increase in irregular migration. Further evidence for this link are the migration networks, which first emerged in the 1990s, however saw a significant expansion in recent years.

Conclusion

The here summarized research intends to add another angle to migration dynamics between Tunisia and Europe. In addition to explaining the phenomenon of irregular migration via economic and political push and pull factors, the researchers add a causal link between protest, particularly its failure, and migration. All interviewees expressed their desperation and mistrust in the political system. Ignoring structural shortcomings, the collapse of the Tunisian currency, the increasing precariousness of the middle class, the repression of social movements, along with failing to review immigration policies that would allow for free movement and legal labour migration, the world is bound to see an even further increase in migration waves, and thus, more tragedies in the Mediterranean Sea.

Français

Français العربية

العربية